Potential Troodon gastric pellets

For immediate release ‐ August 04, 2021

Contact: Jon Pishney, 919.707.8083. Images available upon request

Artistic interpretation of Troodon coughing up a bone-bearing gastric pellet. Illustration: Clarissa Koos.

A new study led by William Freimuth, a PhD student of NCMNS Head of Paleontology Lindsay Zanno, and a team of paleontologists from Montana State University and the University of Washington describes Cretaceous mammals in fossilized gastric pellets potentially produced by the bird-like dinosaur Troodon. These new discoveries demonstrate that Cretaceous mammals were on the menu for dinosaurs like Troodon in Late Cretaceous ecosystems. Additionally, these findings support a number of hypotheses about Troodon life habits and physiology, including crepuscular or nocturnal hunting habits, use of hands or feet during feeding, and near bird-like metabolic levels and digestive processes. These fossil pellets provide a wealth of new information about the paleobiology of mammals and dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous of North America.

You may have dissected owl gastric pellets in elementary school—the regurgitated remains of the bird’s last meal, usually bones, teeth, and fur of small mammals. Although relatively common today, examples of gastric pellets in the fossil record are extremely rare, and connecting a fossil regurgitate to a “regurgitator” is an even trickier task.

A series of recent discoveries, to be published in the journal Palaeontology, provides a rare link between pellets and pellet producer in the fossil record. Researchers identify two fossilized gastric pellets from Egg Mountain, a well-known 76-million-year-old dinosaur nesting site in Montana, USA. The fossil gastric pellets are made up of clusters of bones primarily belonging to the small mammal Alphadon halleyi, a relative of modern marsupials. One pellet contains parts from three individuals, and the second parts of 10 Alphadon and an unidentified lizard. Most bones in the pellets consist of broken jaws, and some limb bones showing signs of etching by digestive acids. These specimens are the oldest known mammal-bearing gastric pellets to date, and the first reported from the Mesozoic.

Who may have eaten and subsequently regurgitated these mammals 76 million years ago? Based on the geological context and fossil record at Egg Mountain, the best candidate as the producer of the fossil pellets is the bird-like dinosaur Troodon formosus. Numerous shed Troodon teeth, as well as egg clutches and other nesting evidence, suggests Troodon may have spent a lot of time in the area—much like living birds of prey who feed and cough up pellets at their favorite roost or nest spots.

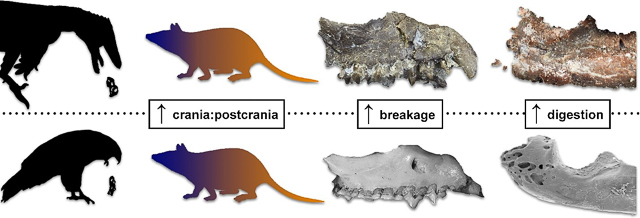

The possible Troodon pellets (top row) share similarities with pellets of extant raptorial birds (bottom row), including an over-abundance of jaws compared to limb bones, high proportions of broken bones, and alteration of bone surfaces attributable to digestive acids. For raptors today, the features of the prey bones are due to handling and tearing chunks of flesh during feeding (instead of swallowing prey whole). Troodon may have fed similarly. Extant mammal bones from Fernández et al. (2012) and Souttou et al. (2012). Click to enlarge.

These mammal-bearing Troodon pellets are important for several reasons. Rather than swallowing its food whole, like owls, the features of the included Alphadon bones suggest Troodon would have handled its food while it fed—perhaps using its feet or hands—in a similar manner to modern hawks, harriers, and kestrels. This feeding behavior may have also occurred at night. Troodon would have had large eyes and excellent vision, and Alphadon (like many other Cretaceous mammals) may have been nocturnal. Finally, these potential Troodon pellets challenge the idea that pellet production in modern birds evolved to reduce their body weight for flight, but instead may have evolved in their flightless relatives to increase their digestive efficiency to accommodate an enhanced metabolism.

An additional, recently published study by Varricchio, Hogan and Freimuth highlights these implications for Troodon life habits in a broader context, in combination with reproductive behaviors and physiology, intelligence, and speculative tool use. These new studies provide fresh insight into how these dinosaurs would have interacted with mammals, other organisms, and their environment during the Cretaceous.

Examples of broken Alphadon jaws from one of the Egg Mountain fossil gastric pellets. Broken tooth-bearing jaws are common in both gastric pellet specimens, likely because teeth are difficult to digest for many predators.

For more information about our upcoming activities, conservation news and ground-breaking research, follow @NaturalSciences on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Join the conversation with #visitNCMNS.