Nature Now! Bagworms: The Misunderstood Insect

For immediate release ‐ November 05, 2020

Nature Now

Contact: Jessica Wackes, 919.707.9850. Images available upon request

By Martie Rose, Intern at the Naturalist Center

Evergreen bagworm. Photo: Matt Bertone.

The Evergreen Bagworm

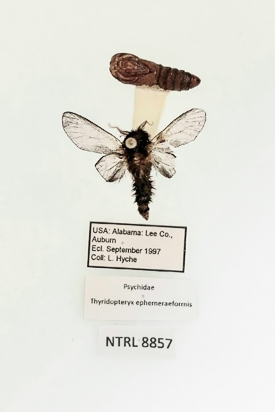

The Evergreen Bagworm (Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis) is a highly misunderstood insect found in the Eastern United States. Worldwide, there are over 1,350 different species of bagworm inhabiting conifer trees such as cypress, juniper, spruce, and pine to name a few. The Evergreen Bagworm may even be in your backyard! Bagworms or bagworm moths are included in the family Psychidae. This family is characterized by being found in case-like structures called bags. Although a fairly small species, bagworms are tiny but mighty. Spending the winter in their mother’s bags as eggs, these insects wait for their grand debut during the summer months. Emerging as caterpillars, they construct their own case made of silk, fecal matter, and debris from the tree in which they are feeding. This creates their own sort of camouflage and protection from predators such as vespid wasps (yellowjackets and hornets) during development. The bags in which they reside also serve as the pupal case in which they metamorphose into adults.

Mature male bagworm moths are black and fuzzy-looking with a wingspan of around one inch. Females at maturity, on the other hand, are wingless, dark brown grub-like insects with sparse hairs. Females also have non-functional antennae, eyes and legs. In late summer, the males will emerge from their bags and seek out females in order to mate. Seeing as the females are wingless, they stay in their bags and mate through the bag openings. The bags also serve as an overwintering case in which the female can store her eggs. The following spring, the eggs develop and the larvae hatch from their mother’s bag and begin to make their own bags!

Pinecones or Bagworms?

Once independent, it’s time to build a bag! The process starts with a long silk strand that the larval bagworm adds leaf and stick debris to that will eventually completely encase them as they dangle from a limb. An opening is left at the top of the bag so the caterpillar can find food, and a small hole is left at the bottom to get rid of excrement until anchoring the bag to get ready for pupation.

The Real Truth

Mature female evergreen bagworm. Photo: Matt Bertone.

Mature male evergreen bagworm. Photo: Matt Bertone.

In an interview with Dr. Colin Brammer of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, I was able to chat about the process of rearing bagworms, preserving them for research, the harsh weather conditions they face and how they deal with them. In regard to rearing these insects it is super easy! Dr. Brammer states, “Literally, pluck some larvae (preferably different ages) off of trees and make sure they have food.” As far as preservation methods are concerned, Dr. Brammer suggests freezing the males to kill them and “simply pinning them like any other Lepidoptera.” For females, it is a bit different as they do not have wings. One must freeze them in their bag and then “put them directly into EtOH or isopropyl alcohol” to prevent decaying. These insects are really easy to find and study, so go outside and try it!

As mentioned before, these insects are tiny but mighty! In harsh weather conditions their silk is so strong, they have the ability to stay attached to their host. For the unfortunate ones, windy days can simply take them to their next host…they just have to hang on for the ride!

Bagworms are very misunderstood insects. Many sources label them as major pests killing different types of conifers in urban areas all over the world! This is taken way out of context. When speaking with Dr. Brammer, he mentioned that he “cannot estimate a single bagworm’s damage but would not believe it is that much.” Dr. Brammer goes on to say that these insects do not “skeletonize” leaves, but can certainly make a tree “not look award winning if populations are large.” All in all, Dr. Brammer has never seen a tree die due to a bagworm infestation, and that it would be a lot more common if it was a serious issue. Therefore, always make sure you are careful when reading about these little buggers. They really get a bad reputation!