Research Yields New Details About Trap-jaw Ants

For immediate release ‐ May 08, 2017

Contact: Jon Pishney, 919.707.8083. Images available upon request

Trap-jaw ants, with their spring-loaded jaws and powerful stings, are among the fiercest insect predators, but they begin their lives as spiny, hairy, fleshy blobs hanging from the ceiling and walls of an underground nest. New research provides the first detailed descriptions of the larval developmental stages of three species of Odontomachus trap-jaw ants. This work was done by scientists at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, North Carolina State University, South China Agricultural University, Sao Paulo State University, and University of Illinois.

While there are nearly 16,000 described species of ants, less than half of one percent of those have had their developmental stages, from egg to adult, described. The number of larval stages of insects is variable, however this study found that workers of the three trap-jaw ant species studied go through three stages of larval development.

The researchers — including Dr. Adrian Smith, head of the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences’ Evolutionary Biology & Behavior Research Lab — determined the number of larval developmental stages, also called “instars,” through measuring hundreds of larval head widths and body lengths and through identifying stage-specific anatomical features through scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

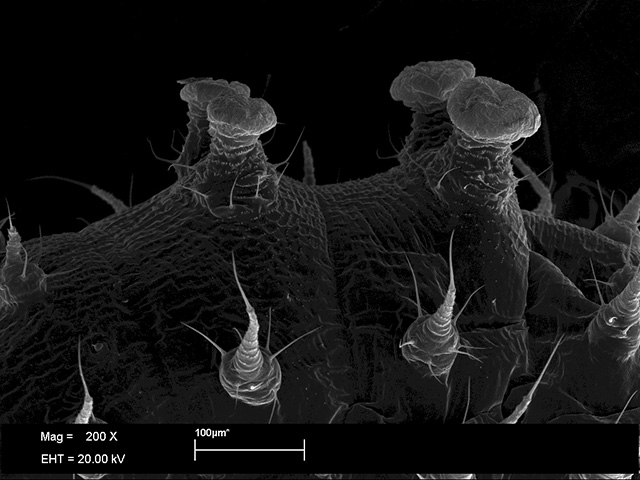

“Door knob” tubercles of the 1st and 2nd instar larvae, used to hang them to the walls and ceilings of the nest.

The SEM images revealed an amazing complexity of body parts such as four “sticky doorknobs” on the backs of 1st and 2nd instars, used to adhere the larvae to nest walls and ceilings; complex “frustrum with spire” hairs of 2nd and 3rd instars; and silk-spinning “pseudopalps” of 3rd instar larva.

Beyond providing the first categorization of larval stages for these ants, surprising results from the work include discovery of the “sticky doorknobs,” which were previously studied in only one other ant species; developmental anomalies such as the appearance of additional doorknob protuberances; and the discovery of a larval parasite found in the gut of a 3rd instar larva.

This research, published by Myrmecological News May 8, provides foundational knowledge that enables future research questions on developmental trajectories, such as when an individual might switch from developing into a worker to developing into a queen. Beyond furthering our understanding of these social insects, the researchers hope the images will inspire interest and appreciation for the complexities of these organisms.