My Museum Mission: A Celebration of Women’s History Month

For immediate release ‐ March 31, 2021

Contact: Micah Beasley, 919.707.9970. Images available upon request

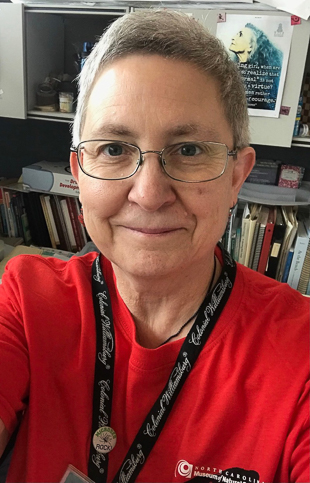

By Deb Bailey, co-coordinator of the Micro World iLab

Recently a colleague told me that based on my interests I would qualify as a Renaissance man (if only I had lived during the Renaissance, and if only I were a man).

My take on life has always been: anything any boy could do, I could do as well or better. And if you tell me I can’t do something, that is a gauntlet thrown down for a challenge I will accept (and prove you wrong). Perhaps I could be considered a feisty Renaissance person today, but based on my beginnings, that outcome was far from assured.

Back then I had the makings of a Renaissance child, but a quiet, shy and withdrawn one. Who I was at my core was kept hidden inside, with only glimpses showing every now and then. An elementary teacher once called me a dreamer, and I was one. One moment I was Robin Hood or Ivanhoe, then Nancy Drew and yet another moment I was a 12-year-old Thomas Edison in the baggage car of a passenger train to Detroit in 1859. At the time, Edison worked on the train selling candy and newspapers to passengers — newspapers he wrote and printed — and spent the rest of his time in the baggage car doing chemistry experiments in a makeshift lab, at least until he set fire to it. From the moment I read that, I wanted a chemistry lab in our basement.

Despite my shyness there were things that set my soul on fire: a small microscope with slides of underwater creatures; my Jon Gnagy drawing set; a dissecting kit and chemistry set; the Mickey Mantle baseball bat I got from a Yankees game; my father’s ham radio set with its dials and Morse Code key. I would even save my allowance to go to the hobby shop to buy specimens to dissect. So, my love of all things literature- and science-related came naturally to me.

My father helped to foster this love of science in some ways: trips to museums, rock quarries, Marconi’s wireless site on Cape Cod and even Edison’s laboratory in Menlo Park, NJ.

Other things, at home and in my world, were not so good. The culture and times were particularly patriarchal: men ruled, women submitted. And Women’s Liberation was only just beginning. Even by the time I graduated from college, it had only been a couple of years since a woman could get a credit card in her own name without a man co-signing for her. Despite my early passion for so many things, by my early teens I was silent and giving up hope.

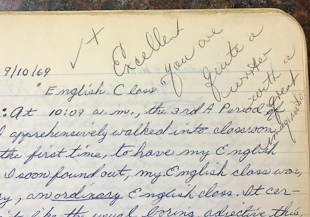

Then came my lifeline. A woman: a young, strong, razor-sharp, intelligent woman who was my high school English teacher. That first day of class she strode to the front of the room, exuding power, competence and passion for her subject, and I was awe-struck. Blown away. I had never seen any woman in my surroundings who carried herself with such confidence, and with such certainty that she deserved to be confident and powerful. At the same time, she was nurturing, insightful, spotted kids who needed that extra help and caring, and gave it willingly. Imagine, a woman who could be both strong and nurturing. In my experience, I had only known strong men and weak women. This teacher gave me the first glimpse of what a woman could be if she wanted to and she became my role model for life.

There were men and other women along the way who helped, guided and mentored. But none came close to that teacher. She saved my life. I went on to graduate college in Medical Laboratory Technology, and worked for years in hospital laboratories and research laboratories. I moved on to Glaxo and worked on one of the early AIDS drugs when there were so few available. From there I spent 10 years on a medical ethics board protecting people in research studies. Always, always I was aware of my teacher’s example: be strong, be competent, care about who you were working with and for. I tried to live up to the example she provided me. I know that through those jobs all those years, I was able to affect the health and safety of thousands of people.

I left those jobs behind though. It was time for my most important role: reaching out to kids. All my life, I was gaining important science experience for the job I do now: co-coordinator of the Micro World Investigate Lab at the Museum’s downtown Raleigh location. I feel as if I’ve finally come full circle back to the teens, but on the other side, providing for teens the two most important qualities my teacher gave to me: hope and an example. That is what my mission at the Museum has been for the past 12 years (three as a volunteer, nine as a full-time educator) reaching out to and offering hope to kids and saying thank you to the Universe for the gift of that teacher who made all the difference in my life.

Now, my education lab is that “science playground” that I dreamt of years ago, like Thomas Edison’s lab on the train — only much safer! My mission for the rest of my time at the Museum is to pay it forward, the only way I can ever say the proper ‘thank you’ to the teacher who saved my life. So, for you, Terry Doyle, thank you. Even now you set a great example for retirement — staying strong with walks, travels, golf and art; so many passions. I honor you. And for all the kids out there: come visit us! We are here for you.