Gut Check Time: New technology used to study endangered Atlantic sturgeon

For immediate release ‐ January 22, 2021

Contact: Jon Pishney, 919.707.8083. Images available upon request

Atlantic sturgeon. Illustration: Duane Raver.

Fossil evidence shows that sturgeon have been around for nearly 175 million years, and likely thrived as marine neighbors of the dinosaurs. It’s no wonder then that they look prehistoric, with five rows of daunting diamond-shaped plates running the length of their bodies. In more recent history, however, sturgeon have had a difficult time.

During the late 1800s people flocked to the eastern U.S. in search of caviar. This “Black Gold Rush” decimated the once-thriving Atlantic sturgeon population, as their eggs were particularly valued as high-quality caviar. Their populations continued to decline through the 1900s, primarily due to overfishing and habitat loss, and they were added to the federal Endangered Species List in 2012.

Hatching in freshwater rivers from Maine to Florida, Atlantic sturgeon head out to sea as juveniles, and return to their birthplace to spawn, or lay eggs, when they reach adulthood. While Atlantic sturgeon can be robust in size – reaching up to 16 feet in length and weighing up to 800 pounds – they are slow-growing and late-maturing, making spawning season all that more crucial to their overall survival.

Conservation scientists use a variety of innovative partnerships and techniques to study, protect and recover these endangered fish. That’s how Dr. Heather Evans, a conservation geneticist for North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission who works in the Museum’s Genomics Research Lab, ended up joining forces with Aaron Bunch from the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources and other colleagues.

Blue catfish share, but are not native to, the waters where Atlantic sturgeon go to spawn, having been introduced to the area in the 1970s as sport fish. In Virginia, there has been a longstanding question about the effect blue catfish have on the Atlantic sturgeon population. Bunch and Evans sought data that would help determine if and how much consumption of sturgeon is occurring.

Evans explains that traditional analysis of the stomach contents of other species of fish was limited to visual identification under a microscope, which is challenging at best, only possible within 24 hours of ingestion, and rarely if ever results in identification of early life stages because those small, soft tissues digest in the stomach extremely rapidly.

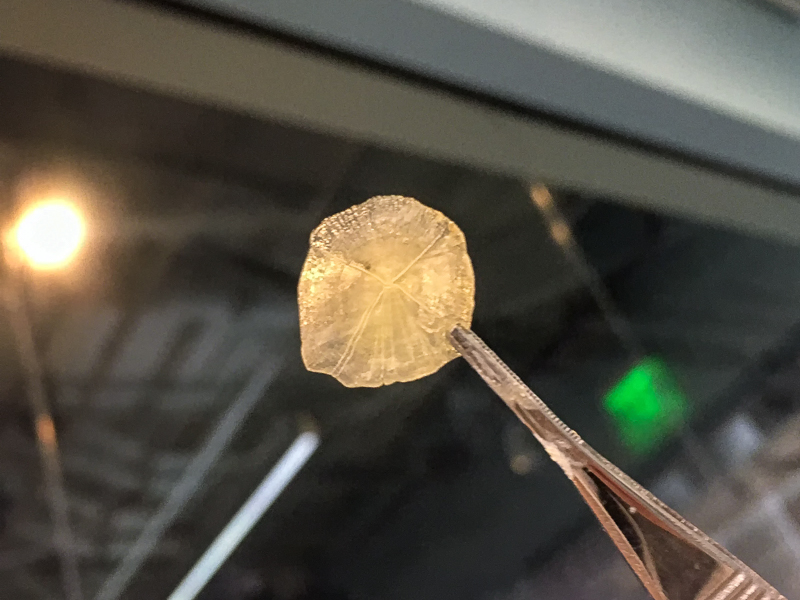

Fish scale extracted from a fish stomach the traditional way, via dissection.

That’s why, when Bunch and Evans proceeded with their recent study, they relied on a relatively new technique called high-throughput (or next-generation) sequencing, which can detect even the smallest DNA evidence of sturgeon, even early life-stage sturgeon, ingested by other fish – and not only from the stomachs but also from the entire digestive tracts.

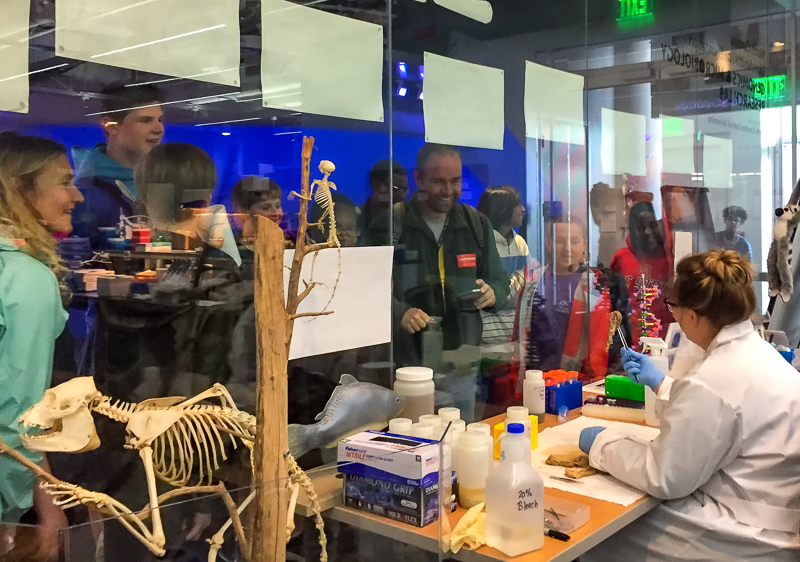

Inspecting the stomach contents of a fish for Atlantic Sturgeon remnants, with an audience.

Out of 559 individual fish sampled from 19 different fish species collected from Virginia’s Pamunkey River, they found evidence of Atlantic sturgeon (ATS) DNA in only 22 samples (4%). The most likely consumers recorded were common carp, with ATS DNA identified in 6 of 52 fish (12%) and blue catfish, with ATS DNA identified in 8 of 134 fish (6%). Not, Evans says, a level of predation one would expect if fish species were actively seeking Atlantic sturgeon as a food source.

So, for now, evidence that blue catfish have an inordinate impact on the survival or recovery of Atlantic sturgeon is lacking. “The study was not about implicating a certain species,” Bunch notes. “It was about getting the data out there and looking across the fish assemblage, whether native or non-native.”

The next step, Bunch adds, will be to apply the species-specific percentages obtained in the study to the overall abundance of each species in order to estimate the total number of occurrences that sturgeon early life stages were consumed and thus determine the impact consumption levels are having on the Atlantic sturgeon population. “This is no small task and challenging because researchers would need to know how many individuals of each species are present in that section of river.”

Watch part of the extraction process here, if you think you can stomach it.