Nature Now! Dance of the Pink Lady’s Slippers

For immediate release ‐ May 07, 2020

Nature Now

Contact: Jessica Wackes, 919.707.9850. Images available upon request

I met my first pink lady’s slipper in the spring of 1977 in eastern North Carolina. For most of my youth, I didn’t give plants a second look. They were in the background of the forests and swamps that I searched for my favorite critters—reptiles and amphibians. I was a college student on this sunny day in May and home for the weekend. I was exploring some pine woods looking for herps (reptiles and amphibians) with my recently purchased Olympus OM-1 SLR camera loaded with Kodachrome 64 film.

As I made my way through the woods scanning the pine needle floor for any herps about, my eye caught the bright pink color of something ahead. Although I had never seen one before, I knew what it was — a pink lady’s slipper! The flowers are very distinctive, and I had previously seen their photos in books.

Pink lady’s slipper, Cypripedium acaule

Wow! Photos didn’t do them justice! It was an absolutely gorgeous pink flower set against the brown background of pine needles. And it was a whole “ballroom” of pink lady’s slippers! Several dozen were scattered in the area — some “wallflowers” by themselves, others in pairs or small groups of three to six scattered on the “ballroom floor” in a beautiful dance of color.

Pink lady’s slipper, Cypripedium acaule, is one of many native orchid species in North Carolina. Their distribution includes much of the northeastern United States extending up into Canada. They also follow the Appalachian Mountains southward into Alabama and Georgia. In North Carolina they are found in the mountain and in portions of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain. Not rare, but uncommon enough to delight almost everyone who finds one in the wild. They need acidic soils to thrive, doing best at soil pH’s of 5 or less. They are often found under pines or other conifers whose decaying needles contribute to the acidity of the soil.

I discovered a population of pink lady’s slippers a few years ago near where I now live. This has given me the opportunity to watch the individuals in this population go through their annual life cycle. I enjoy seeing when the first new leaf bundles emerge from the ground and then send their graceful flowers up for all to see. The developing flower is at first a very light greenish color, before it slowly blushes to a beautiful shade of pink. Some must have more to blush about than others as they end up with different shades of pink!

Spring emergence of pink lady’s slippers.

Young developing flowers transition from a light green to pink as they mature.

Pink lady’s slippers are perennials, which means that the plant sprouts from the same root on an annual cycle. It’s the same plant, with new leaves and flowers each year. They flower from April through May, depending on location. The leaves and flowers of the pink lady’s slippers “die” after their spring emergence, withering away to nothing. If successfully pollinated, they will leave a seed capsule at the tip of the original flower stem loaded with seeds ready for dispersal. The plant spends the winter underground in root form until the next year.

Some individual plants sprout from the root earlier than others. Some will be in full flower while others are just breaking through the leaf litter. Perhaps this spreads out the time when flowers are available to pollinators.

Bees are the main pollinators for pink lady’s slippers.

Bees, particularly bumble bees, are the main pollinators of pink lady’s slippers. The flower appears to be designed for such large bees. The bee is attracted to the bright pink flower thinking thoughts of sweet nectar. There is a slit-like opening in the front of the highly modified flower petal, perfect for a bee to crawl through after landing on the flower. Once inside the large pouch-like chamber, the bee finds no nectar and is trapped! It must work its way up to exit a small opening at the top of the flower. This exit is tight for the bee and causes the bee to rub against a pollen laden structure. The now pollen bearing bee will fly to another flower hoping for a nectar reward again. Finding no reward, again, it works its way up and out of the flower. This time some pollen from the previous flower may rub off on the stigma part of this flower thus pollinating it. The bee may pick more pollen from the second flower to carry to the next one, if it hasn’t learned the lesson that these flowers have no nectar.

Highly modified petal has a front slit for bees to enter.

Bees find that their best exit is an opening at the top of the flower.

Inexperienced bees are probably the main pollinators for pink lady’s slippers! Once they learn there is no nectar in this type of flower, they probably don’t bother to try again. I don’t know how many times it takes the bee to learn this, but the same bee must visit at least two flowers for any pollination to occur! I have never seen this in person but have read a first-hand account. I keep hoping to hear the buzz of a trapped bee in one of the pink lady’s slippers near my home. When I do, I will wait for the bee to work its way out so that I can photograph its embarrassed expression when it emerges from the flower! Hmmm, do embarrassed bees sting?

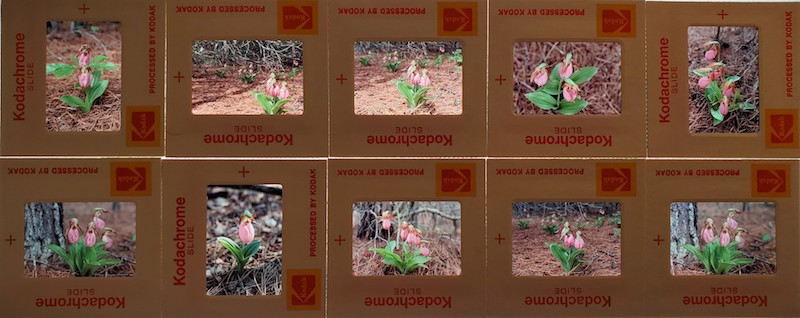

Photo of Kodachrome slides from my first encounter in 1977.

It’s been over 40 years since I saw my first pink lady’s slippers. I still have the original Kodachrome slides that I took that May day in 1977. I am so happy to end up living near an annual dance of these lady’s slippers years later. I hope the band keeps on playing for this population and others so that future generations of humans can enjoy their dance for many more decades.

By Jerry Reynolds, Head of Outreach

For more information about our upcoming activities, conservation news and ground-breaking research, follow @NaturalSciences on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Join the conversation with #visitNCMNS.