Ancient Carpet Shark Discovered with ‘Spaceship-Shaped’ Teeth

For immediate release ‐ January 21, 2019

Contact: Tracey Peake, NCSU News Services, 919.515.6142 and Terry Gates. Images available upon request

Galagadon, (c) Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum.

Galagadon, (c) Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum.

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL JAN. 21, 2019 AT 8:00 A.M. EST

The world of the dinosaurs just got a bit more bizarre with a newly discovered species of freshwater shark whose tiny teeth resemble the alien ships from the popular 1980s video game Galaga.

Unlike its gargantuan cousin the megalodon, Galagadon nordquistae was a small shark (approximately 12 to 18 inches long), related to modern-day carpet sharks such as the “whiskered” wobbegong. Galagadon once swam in the Cretaceous rivers of what is now South Dakota, and its remains were uncovered beside “Sue,” the world’s most famous T. rex fossil.

“The more we discover about the Cretaceous period just before the non-bird dinosaurs went extinct, the more fantastic that world becomes,” says Terry Gates, lecturer at North Carolina State University and research affiliate with the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Gates is lead author of a paper describing the new species along with colleagues Eric Gorscak and Peter J. Makovicky of the Field Museum of Natural History.

“It may seem odd today, but about 67 million years ago, what is now South Dakota was covered in forests, swamps and winding rivers,” Gates says. “Galagadon was not swooping in to prey on T. rex, Triceratops, or any other dinosaurs that happened into its streams. This shark had teeth that were good for catching small fish or crushing snails and crawdads.”

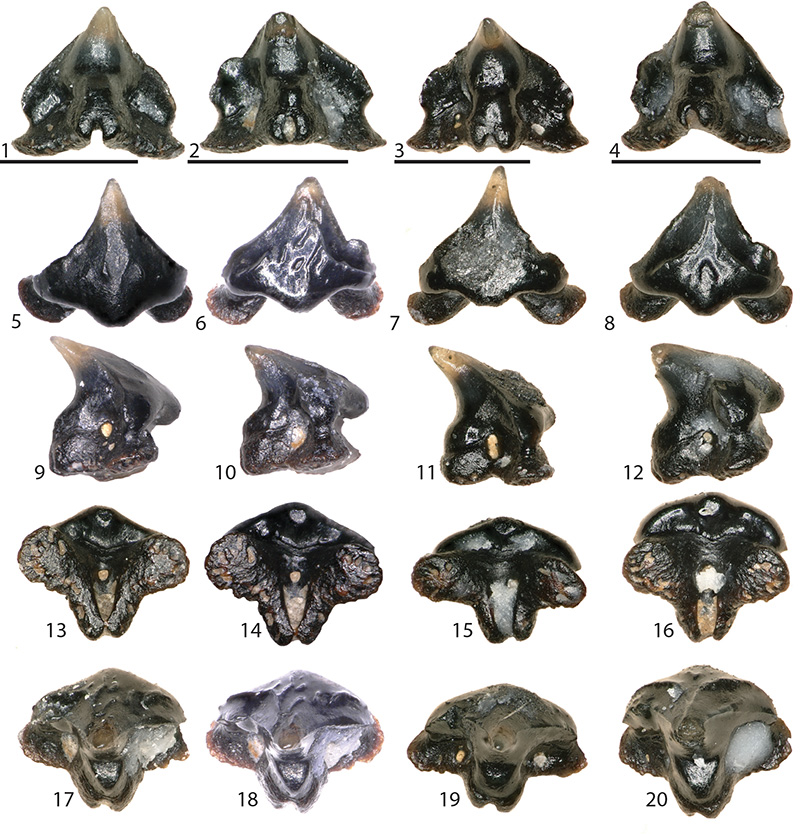

The tiny teeth – each one measuring less than a millimeter across – were discovered in the sediment left behind when paleontologists at the Field Museum uncovered the bones of “Sue,” currently the most complete T. rex specimen ever described. Gates sifted through the almost two tons of dirt with the help of volunteer Karen Nordquist, whom the species name, nordquistae, honors. Together, the pair recovered over two dozen teeth belonging to the new shark species.

“It amazes me that we can find microscopic shark teeth sitting right beside the bones of the largest predators of all time,” Gates says. “These teeth are the size of a sand grain. Without a microscope you’d just throw them away.”

Despite its diminutive size, Gates sees the discovery of Galagadon as an important addition to the fossil record. “Every species in an ecosystem plays a supporting role, keeping the whole network together,” he says. “There is no way for us to understand what changed in the ecosystem during the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous without knowing all the wonderful species that existed before.”

Gates credits the idea for Galagadon’s name to middle school teacher Nate Bourne, who worked alongside Gates in paleontologist Lindsay Zanno’s lab at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences.

The work appears in the Journal of Paleontology and was supported in part by the National Science Foundation.

Note to editors: An abstract of the paper follows.

Galagadon teeth. Image: Terry Gates.

Galagadon teeth. Image: Terry Gates.

“New sharks and other Chondrichthyans from the latest Maastrichtian (Late Cretaceous) of North America”

DOI: 10.1017/jpa.2018.92

Authors: Terry Gates, North Carolina State University; Eric Gorscak, Peter Makovicky, Field Museum of Natural History

Published: Journal of Paleontology

Abstract:

Cretaceous aquatic ecosystems were amazingly diverse, containing most clades of extant aquatic vertebrates as well as an array of sharks and rays not present today. Here we report on the chondrichthyan fauna from the late Maastrichtian site that yielded the Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton FMNH PR 2081 (“SUE”). Significant among the recovered fauna is an unidentified species of carcharhinid shark that adds to the fossil record of this family in the Cretaceous, aligning with estimates from molecular evidence of clade originations. Additionally, a new orectolobiform shark, here named Galagadon nordquisti n. gen n. sp., is diagnosed on the basis of several autapomorphies from over two-dozen teeth. Common chondrichthyan species found at the ‘SUE’ locality include Lonchidion selachos and Myledaphus pustulosus. Two phylogenetic analyses (Maximum Parsimony and Bayesian Inference) based on twelve original dental character traits combined with 136 morphological traits from a prior study of 28 fossil and extant taxa, posited Galagadon in two distinct positions: as part of a clade inclusive of the fossil species Cretorectolobus olsoni and Cederstroemia triangulata plus extant orectolobids from the Maximum Parsimony analysis; and as the sister taxon to all extant hemiscyllids from the Bayesian Inference. Model-based biogeographical reconstructions based on both optimal trees suggest rapid island hopping-style dispersal from the Western Pacific to the Western Interior Seaway of North America where Galagadon lived. Alternatively, the next preferred model posits a broader, near-global distribution of Orectolobiformes with Galagadon dispersing into its geographic position from this large ancestral range.