Armored archosaur discovery reveals complexity of dinosaur origins

For immediate release ‐ August 03, 2023

Paleontology

Contact: Jon Pishney, 919.707.8083. Images available upon request

Original news story published August 3, 2023. Updated November 20, 2023.

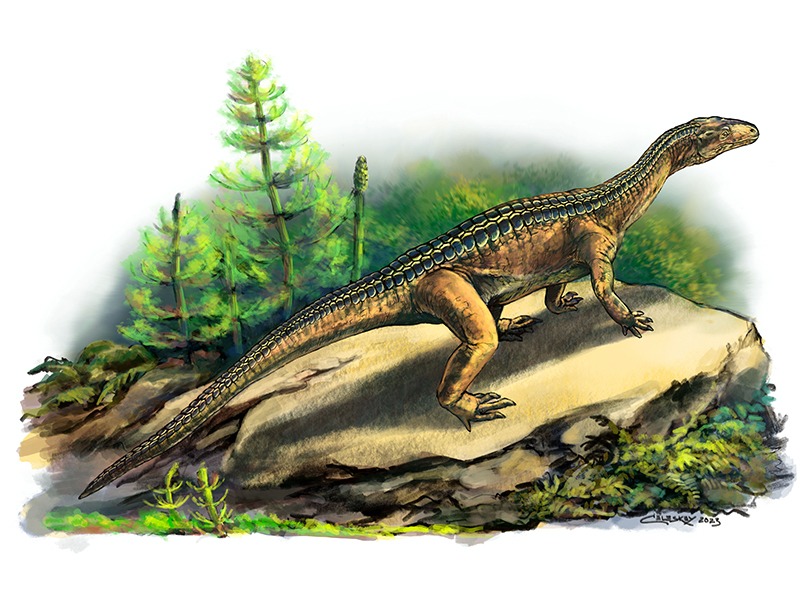

Illustration of Mambachiton fiandohana as it may have looked in life, showing the characteristic paired scutes along its back. Art by Matt Celeskey.

Illustration of Mambachiton fiandohana as it may have looked in life, showing the characteristic paired scutes along its back. Art by Matt Celeskey.

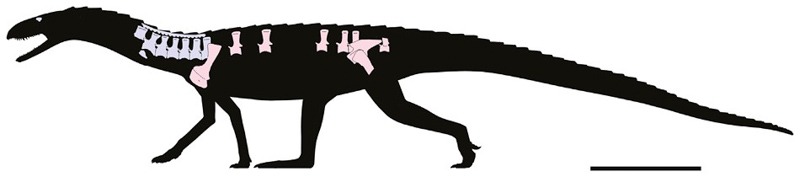

A team of American and Malagasy researchers, including NCMNS Research Curator of Paleontology Dr. Christian Kammerer, have discovered a new species of prehistoric reptile that provides important information on the early history of the dinosaur lineage. The new species, Mambachiton fiandohana, was discovered during fieldwork in the Morondava Basin in southwestern Madagascar. It dates back to the Triassic Period, roughly 235 million years ago. Mambachiton would have been a long-necked, quadrupedal animal, and is estimated to have been 4–6 feet (1.5–2 meters) long and weighed between 25–45 pounds (10–20 kilograms).

Silhouette reconstruction of Mambachiton fiandohana, showing the recovered bones of this species in blue (neck vertebrae-preserving armor) and pink.

Silhouette reconstruction of Mambachiton fiandohana, showing the recovered bones of this species in blue (neck vertebrae-preserving armor) and pink.

The most interesting aspect of this new species is the presence of bony armor plates, called osteoderms or scutes, atop its vertebrae. Although armor is known in a variety of dinosaurs, it is usually considered a relatively late innovation in dinosaur evolution, first appearing in the Jurassic Period. Previously, all known specimens of Triassic dinosaurs and their close relatives were unarmored, a feature distinguishing them from their distant living relatives the crocodiles. Mambachiton shows that the common ancestor of both dinosaurs (including birds) and crocodiles was armored, and that the presence of armor had a complex evolutionary history in the larger dinosaur-crocodile lineage (called archosaurs). Ancestrally present in animals like Mambachiton, it was lost for most of early dinosaur history, then re-appeared independently in some later dinosaur groups.

“The loss and re-evolution of armor is an important aspect of the story of dinosaur evolution—freeing them from some of the biomechanical body constraints of ancestral archosaurs and potentially contributing to some of the locomotor shifts as dinosaurs diversified into a dizzying array of different ecologies and body forms,” said Dr. Kammerer.

“Mambachiton demonstrates that retention of ancestral features or acquisition of new traits depend on interactions within the ecosystem,” said project co-leader Dr. Lovasoa Ranivoharimanana of the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar. “When a character is essential, it is retained, but when it is no longer useful, it disappears.”

Mambachiton is the latest addition to an extremely rich fauna of Triassic animals from southwestern Madagascar. Other fossil species found at this locality include Kongonaphon, a squirrel-sized, bipedal archosaur related to the flying pterosaurs, the beaked, plant-eating reptile Isalorhynchus, and a variety of synapsids, the group including animals and their extinct relatives. “Fossils from Madagascar are very important for our understanding of what is happening globally during the Triassic”, said Dr. Kammerer. “Most fossils of this age come from South America, making it hard to tell if the observed faunas there are typical of the time period as a whole, or are unique to one region. Fieldwork in understudied regions with Triassic outcrops are vital to reconstructing the evolutionary history of a variety of animal groups—dinosaurs, crocodiles, mammals—around the time of their origination.”

Co-authors on the study included Sterling Nesbitt from Virginia Tech, Emily Patellos from the University of Southern California and Virginia Tech, John Flynn from the American Museum of Natural history, and André Wyss from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Funding or other support was provided in part by the National Geographic Society (grant #s 5957-97, 6271-98, and 7052-01); World Wide Fund for Nature/World Wildlife Fund, Madagascar; the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History; and the Field Museum of Natural History Meeker Family Fellowship. The joint Madagascar-U.S. paleontological exploration, research, and education program was supported by the Université d’Antananarivo, Ministère de L’Enérgie et des Mines, and ICTE/MICET (Madagascar), and the American Museum of Natural History, Field Museum of Natural History, and University of California-Santa Barbara (U.S.).

Link to paper: https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad038

For more information about our upcoming activities, conservation news and groundbreaking research, follow @NaturalSciences on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.