Nature Now! Taken for Granite

For immediate release ‐ June 11, 2020

Nature Now

Contact: Jessica Wackes, 919.707.9850. Images available upon request

I’m not a geologist but I don’t take for granted how important geology is to life on Earth. Present day North Carolina is the result of a long history of geologic events involving erupting volcanoes, continental collisions and sedimentation along with lots of weathering and erosion! The diversity of life in natural areas is the result of the interactions of geology, climate and living organisms.

Eastern Wake County and much of Franklin County is very much influenced by the presence of one huge mass of granite. This large body of granite even has a name — the Rolesville batholith! It is about 50 miles long, up to 15 miles wide and who knows how deep! Even my house in western Johnston County is over the southeastern edge of this granite body. I know this by reviewing maps produced by the North Carolina Geologic Survey in addition to seeing granite peeking out in my neighbors’ yards. Large granite boulders are also visible in scattered locations in nearby woods.

Boulders in Johnston County woods

Granite is an igneous rock type which means that it formed from the cooling of magma (molten rock). It is primarily composed of quartz, feldspar and mica. The Rolesville granite formed along with other granite bodies in the southern Appalachian region around 300 million years ago. The magma was created from the very slow but tremendous collision of the continental plates that pushed up the Appalachian Mountains. The magma cooled underground and probably never reached the surface at the time. Weathering and erosion of the overlying rock eventually exposed this granite body. Granite itself weathers too, eventually leaving only clay and quartz sand.

Mitchell Mill State Natural Area

The areas where large granite bodies are exposed are known as granite domes or granite flatrocks. Stone Mountain is one of the more well-known granite domes in the lower elevation mountains. Granite flatrocks are lesser known and occur as relatively flat exposures of granite in scattered localities in the piedmont area of North Carolina. Most are very small, up to a few acres of exposed granite, but Mitchell Mill State Natural Area has almost 20 acres of exposed granite. I first visited this area as a college student in the ‘70s. This was a regular field trip for biology classes to study the ecological process of primary succession, the orderly sequence of fungal and plant life colonizing an area where none occurred before. The colonization of bare rock first by lichens and mosses, then more advanced vascular plants and eventually woody plants is a textbook example of primary succession.

Lichens and mosses are the first to grow on the bare granite

The process can lead to a mature plant community above the rock surface but can get reset to “zero” by wind or water events that strip the plants off the bare rock. At Mitchell Mill State Natural Area, the Little River does this periodically with flooding events during times of heavy rainfall. Granite flatrocks and domes have been around long enough that some plants have adapted to only live on these harsh environments. With names like elf orpine and Appalachian sandwort, some of these plants are only found on these granite exposures. Their rarity is because of the rarity of such granite exposures.

Elf Orpine and Appalachian Sandwort (white bloom)

Perhaps the easiest place to see exposures of granite flatrock is at the Main Street Park in Rolesville. If you hike the trails you will come across several exposures of granite hinting at the massive granite body underneath the town and surrounding countryside.

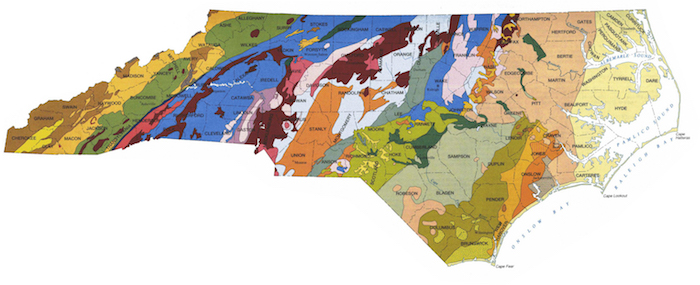

If you are curious about the geology and type of rock where you live, check out the geologic map of North Carolina available from the North Carolina Geological Survey. You will see an array of colors reflecting the rich geological diversity of our state. Don’t take geology for granite, unless it is!

Generalized Geologic Map of North Carolina; pink blob covering eastern Wake and most of Franklin Counties is the Rolesville batholith

Generalized Geologic Map of North Carolina; pink blob covering eastern Wake and most of Franklin Counties is the Rolesville batholith

By Jerry Reynolds, Head of Outreach

For more information about our upcoming activities, conservation news and ground-breaking research, follow @NaturalSciences on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Join the conversation with #visitNCMNS.