Nature Now! March of the Mayapples

For immediate release ‐ May 01, 2020

Nature Now

Contact: Jessica Wackes, 919.707.9850. Images available upon request

March is the month when I first see mayapples emerge from the forest floor behind my home in Johnston County. For me, they show up right after the peak of the early spring spawning of Least Brook Lamprey in my little stream. (That’s another story!) Their emergence is quite magical as little green knobs start to appear on what previously was a bare leaf-covered forest floor.

The mayapples have been there all along, as a network of underground stems called rhizomes connected to a central root system. I’ve been walking on them since last year’s plants “disappeared” in the late spring. Most people do not have a clue about what is lurking under their feet when they hike across a mayapple bed in the fall or winter.

Podophyllum peltatum, in the family Berberidaceae, is most commonly known as mayapple, may-apple or mandrake. Some people may call it umbrella-leaf because of the shape of its leaves but that name is usually used for its less common close relative, Diphylleia cymosa.

Mayapple occurs in much of the eastern United States and even up into southeastern Canada. In North Carolina it is found in forests, stream bottomlands and pastures across our state. Spring arrives early in the coastal plain so mayapples emerge here first. This wave of emergence is a slow westward march to the higher elevations in our state and a northward march to the higher latitudes of our northern states.

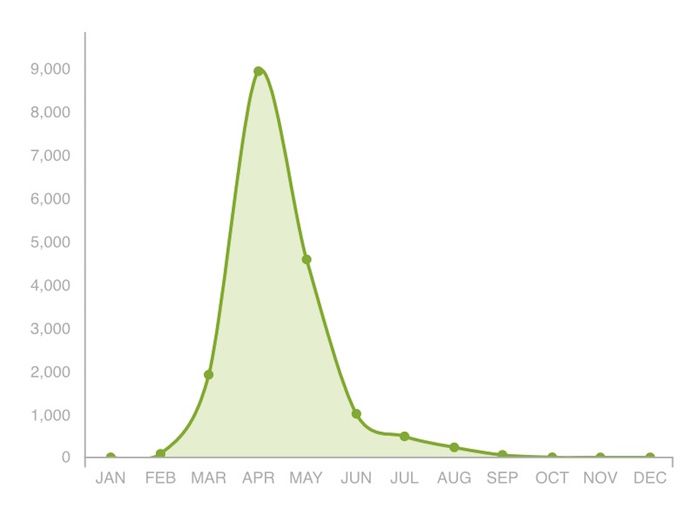

I have friends in the western part of the state and in more northern states such as Illinois. I post on social media when my mayapples first emerge. My friends are quick to chime in that theirs have not made an appearance yet. Then I see the later posts when their mayapples have appeared. The study of this phenomenon of seasonal variation of emergence, blooming or even activity (animals) is known as phenology. You can look at the timeline of observations of mayapples on iNaturalist and see that observations begin in February, make a steep climb in March to an April/May peak before dropping quickly to much lower numbers in June/July.

Once the mayapple emerges and unfurls its large leafy umbrellas, it’s hard not to notice. Rising up over a foot above the forest floor on a single stem to a single or double leaf, they make their presence known! The palmately-lobed leaves look like miniature palm trees on the forest floor after they have first unfurled their canopy.

Those leaves can grow to be 8 inches or more in diameter and they hide the mayapple’s beautiful flower when it blooms. If you get down and look under that layer of broad leaves, you will see that there is a single white flower on a short stalk emerging from the fork of the double leafed stems. Only older plants with two leaves produce flowers. The single leafed mayapples are younger and do not produce flowers.

The name “mayapple” was probably given because it blooms in May, at least in the more northern latitude or higher elevation populations. My mayapples bloom in March and I jokingly refer to them as “Marchapples”! They develop fruits in April which ripen in May, thus “mayapple” seems an appropriate name again. I usually do a weekend trip to the mountains in early May. After watching my mayapples emerge, grow, bloom and fruit behind my house at an elevation of only 230 feet earlier in the spring, I enjoy seeing the mayapples blooming in May in the higher elevations of our mountains.

When you see a patch of mayapples, it may only be one plant! They first grow from a central root system but spread as their rhizomes grow laterally underground in a slow march to colonize the forest floor. The mayapples that you see emerge from the forest floor are sprouting from those rhizomes of the same plant. So that wonderful green patch of dozens or more mayapples may be just one mayapple plant!

All parts of the plant are poisonous, except for the fruit once it ripens. The plants contain podophyllotoxin which historically and presently has a variety of medicinal uses including promise in the treatment of some cancers. The ripe fruits are eaten by a variety of animals and probably are a favorite of the eastern box turtle. The hanging fruits are just about the right height for a box turtle to reach up and grab for a “take-off” meal. The box turtle may provide a means of seed dispersal by later pooping out the seeds in other parts of the forest.

So, I look forward to March each year when the march of the mayapples begins in my backyard and continues across the state well into May. I hope that they have “marched” to a natural area near you!

By Jerry Reynolds, Head of Outreach

For more information about our upcoming activities, conservation news and ground-breaking research, follow @NaturalSciences on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Join the conversation with #visitNCMNS.