Waterdog Warriors

For immediate release ‐ December 30, 2022

Contact: Melissa Dowland, melissa.dowland@naturalsciences.org. Images available upon request

By Melissa Dowland, NCMNS Manager of Teacher Education

Beneath the reflected branches of riparian trees in the tinted waterways of Wake and Johnston County, something slimy lurks. Hiding beneath rocks and fallen trees, in places you’d likely spare no second thought for, lives one of North Carolina’s most unusual animals. Neuse River waterdogs are aquatic salamanders, spending their entire lives in streams and rivers. Their golden brown bodies are blotched with darker spots and their four small limbs are almost an afterthought, allowing them to blend in with the earth tones of their riverine habitat. But with brilliant red, feathery gills and a wide mouth that almost looks like it’s smiling at you, you can’t help falling in love. Which is exactly what we hoped to accomplish when we dragged thirteen teachers from ten North Carolina counties out into the field on a cold gray weekend in mid-December.

Neuse River waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Neuse River waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Perhaps dragged isn’t the right word. Because after spending Saturday morning at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences learning about waterdogs through a combination of hands-on activities and an engaging presentation, each person involved in our Waterdog Warriors Educator Trek was hopeful that we’d get the chance to see one of these incredible animals in the wild. On Saturday afternoon we set the stage as the teachers worked with Eric Teitsworth, an NCSU graduate student studying the species, to set 40 minnow traps baited with chicken livers (a favorite food of both Neuse River waterdogs and my 90-year-old mother-in-law) at two of his research sites along the Little River. These were at places where he had successfully marked and released waterdogs in earlier years of his study, so we crossed our fingers that they’d be there again.

Hannah, an educator in eastern NC, tosses a minnow trap into the Little River. Photo: Megan Davis/NCMNS.

Hannah, an educator in eastern NC, tosses a minnow trap into the Little River. Photo: Megan Davis/NCMNS.

The waterdogs didn’t disappoint! After a Sunday morning tour of the Museum’s herpetology collection and a presentation from Jennifer Archimbault, the lead biologist for this federally threatened species at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, we returned to the Little River to check our traps. It was chilly, with temperatures in the 50s and gray skies, but as we pulled the first trap out of the river and heard Eric holler that it held a Neuse River waterdog, a cheer went up. The weather was forgotten as the salamander paparazzi quickly converged. Eric and his field technicians demonstrated their data collection process: weighing, measuring, photographing, and tattooing (with a visible implant elastomer that has been safely used in similar applications for many years). As the afternoon progressed, we captured an additional four waterdogs, which our excited educators were able to help process (though the tattooing was left to the experts).

Our first waterdog – call in the paparazzi! Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Our first waterdog – call in the paparazzi! Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

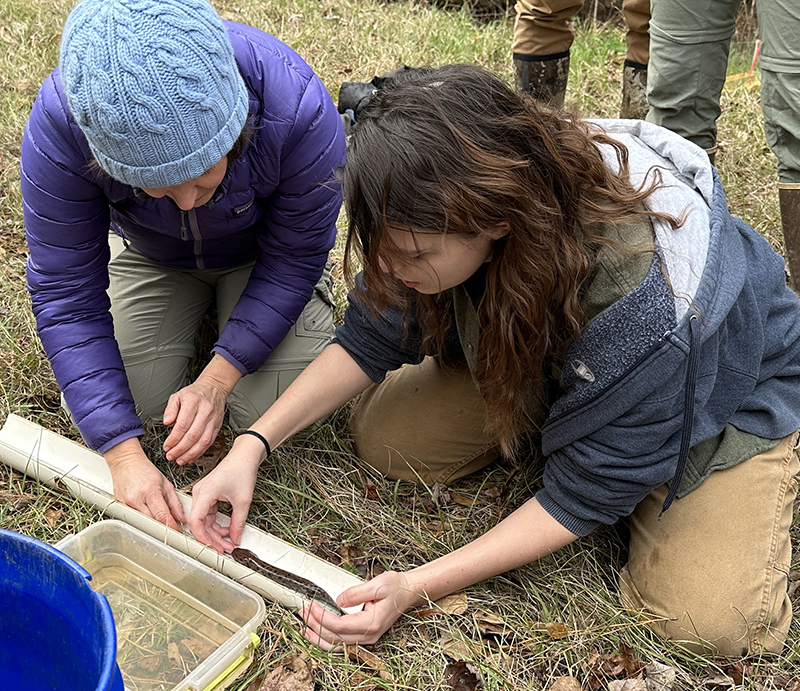

Kelly, a teacher from Orange County, helps Caitlyn, a research technician for the project, measure the length of a waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Kelly, a teacher from Orange County, helps Caitlyn, a research technician for the project, measure the length of a waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Mika, a teacher from Durham, takes data on a captured waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Mika, a teacher from Durham, takes data on a captured waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Why waterdogs, you may wonder? The Neuse River waterdog is a North Carolina endemic species, meaning that it only occurs in North Carolina. In fact, it is only found in the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico River Basins in central and eastern North Carolina. Much of the early work on this species was done by Alvin Braswell, former Museum Director and emeritus Curator of Herpetology for the Museum, who also joined us for the workshop. His early work laid the foundation for more recent studies that showed a decline in the Neuse River waterdog population, likely linked to an increase in sedimentation and pollution as we clear and develop land in their range. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has listed the Neuse River waterdog as a federally threatened species, meaning that it is at risk of becoming endangered in the foreseeable future. By giving educators the tools and knowledge to teach about this remarkable and rare species, we hope to raise public awareness and increase support for the species’ survival.

Giving a waterdog a tattoo for future identification. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Giving a waterdog a tattoo for future identification. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Researchers use a visible implant elastomer to tattoo each waterdog in a specific color pattern to help with identification if the animal is recaptured. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Researchers use a visible implant elastomer to tattoo each waterdog in a specific color pattern to help with identification if the animal is recaptured. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

The Waterdog Warriors workshop is part of a bigger program — Project RESTORE (Rescuing Endangered Species through Outreach, Restoration, and Education) — a collaboration between the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the NC Museum of Natural Sciences. Project RESTORE focuses on raising awareness of imperiled species in North Carolina by providing teachers and students the opportunity to learn about and participate in species monitoring and restoration. The Museum, with funding and support from the USFWS Coastal Program, will provide educational programming involving American shad, Venus flytrap, Carolina madtom, Neuse River waterdog and red wolf. The program is funded by the USFWS Coastal Program and coordinated and conducted by the NCMNS.

You too can be a Neuse River Waterdog Warrior by:

- Reducing erosion on your property by leaving trees and plants along the banks of streams.

- Minimizing the use of pesticides, herbicides, and other chemicals.

- Not creating dams or stacking rocks that restrict water flow in streams and creeks.

- Spreading the word about Neuse River waterdogs!

And if you’re not convinced that this slimy salamander deserves your love, doing these things will also help improve water quality in our rivers and streams, and we all depend on clean water — humans and waterdogs alike.

Neuse River waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

Neuse River waterdog. Photo: Melissa Dowland/NCMNS.

For more information about our upcoming activities, conservation news and ground-breaking research, follow @NaturalSciences on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.